Writing software to write software

Since I started my PhD in September, 2015, I have been writing a lot of code. My research project contains its fair amount of theory, but it is significantly practical and applied science, so I need to write software to test things out.

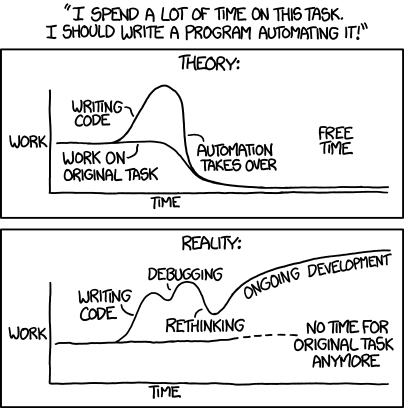

A percentage of my coding was indeed targeted at creating original software that could do something related to my research. Another significant part, however, was about automation:

In my case, doing applied science means I need to iterate, test and evaluate a lot of things on a daily basis. I could do the analysis by hand, or by copying-and-pasting numbers back and forth in Excel. In the short term that works perfectly well, but things start to grow and become more and more error prone in the long run.

In February 2016 I conducted an experiment involving games, facial expressions and heart rate measurements. Each participant spent, on average, 25 minutes in a gaming session, which involved playing 3 different games (two coded from scratch by myself), resting and answering questionnaires. I could be there in the room, with a notebook frantically taking notes of things. Then I would need to transcribe all that information into a spreadsheet to perform further analysis. Again the chances of misplacing numbers here and there is very real (and dangerous), so I wrote a software to run the whole experiment for me.

During the development time, I even spent a few additional precious hours to create a very simple web interface, accessible from my mobile, to monitor the experiment. That was awesome! Even though I was not in the experiment room, I could just light up my phone and see what was happening. Was the participant playing game #2? Or maybe resting? I could enter the room at the precise moment the experiment was over.

Later on I needed to analyze all the data I collected. Solution? I wrote another piece of software to visualize the data (since everything was custom recorded):

![]()

A few months after the experiment, I started a paper about it. I needed several different chunks of data and reports, so I distilled several command line utilities (e.g. analyze and hr2db) that helped me obtain what I wanted. As a side note and honest advice, don’t write crappy and/or undocumented software just because you are the sole user (at the moment). Doing a PhD often involves switching contexts pretty frequently, so at times I only re-used (or coded again) a utility 2 months after its creation. Despite being the author of the tool, it is fair to say I remembered nothing about it after 2 months doing other things. The tool might as well be considered to be written by someone else.

That’s the reason why I tried my best to make the tools at least UX-acceptable with a minimum amount of documentation:

Usage:

php analyze.php [<subjectId>|<firstId>:<lastId>] [options]

Options:

--report Prints the processing as a report.

--csv <file> Saves the processing as a CSV file defined

by <file>.

--export <file> Exports all HR entries as a file defined

by <file>.A few months ago, I had to analyze a database of 530 videos, all containing BDF files unsupported by my software. I needed only the HR from those BDF files. I found several different programs that could convert the files to me, but they required manual interaction with a GUI. Solution? I wrote BDFextractor to extract the HR from BDF files using the command line. Now I could run (another) little software on the database and export the HR from all those 530 files. Victory!

I have been writing lots of R code lately, to perform statistical analysis and plot some charts. I can confidently say I wrote more multi-use support software in the past year than I thought I would.

Writing that much software might be seen as a waste of time, after all there are plenty of solutions out there for virtually everything. Every move demands time, though, be it learning (or developing) a new tool. Time is an incredibly precious resource, so I always choose the option that better accounts for that. Every time I have to write a small tool, I remember the advice from an old saying about chopping off of a huge tree: if you have to do it, you better have the right tools and be sure they are as sharp as they could be. That’s a fact.