Past the Event Horizon - Why "AI Replacing Developers" Is the Wrong Frame

In June 2025, Sam Altman published a blog post titled “The Gentle Singularity,” in which he made a declaration that would have sounded insane just three years prior: “We are past the event horizon; the takeoff has started”. To the uninitiated, this summons images of science fiction—robots walking the streets or a sudden, dramatic rupture in reality. Yet, as Altman noted, the world looks largely the same. Commuters still sit in traffic; we still use Jira; and the physical constraints of the universe remain stubbornly in place.

But for those of us in software engineering, the shift has been anything but gentle. We stand at the intersection of three contradictory narratives:

- Barriers to entry have collapsed, leading to “Vibe Coding” where natural language replaces syntax.

- Labor demand has cratered, with US job postings falling to pre-pandemic lows.

- The developer population is exploding, driven by global adoption and AI integration.

The capability-to-cost curve has shifted. The real question now is: how do we integrate this tool into what we already know about building software—without fooling ourselves with demo-driven thinking?

This post is an attempt to do that, grounded in the latest labor signals, developer-population data, and a critical “third axis” that many discussions ignore: verification cost (and why most GenAI projects still fail).

1) Abstraction doesn’t erase developers — it changes what “developer work” means

A useful historical analogy is the compiler. Before its usage in scale, software was handcrafted on the binary level (or very close to it). As the abstraction improved, developers stopped caring about (or paying attention to) the generated, low-level code. The higher the abstraction (programing languange, paradigm, etc), the less we look down the chain.

We don’t spend much time today arguing “compiled vs interpreted”, or about the “perfect assembly” in the way people did decades ago. That’s because most teams now operate at a higher layer of abstraction. Following that analogy, today’s Java code is the abstraction, not its bytecodes. Same for C, for instance: most of the time (not always, but very significantly) you don’t look at the generated assembly code. It’s simply too low level.

In that sense, compilers or interpreters didn’t eliminate developers; they made it cheaper to create software. That dynamic tends to increase demand. You can see this in how the developer population grew alongside each major abstraction wave.

Evidence: the pool keeps growing

Contradicting the narrative of “AI replacing humans” is the relentless growth of the global developer population. According to SlashData’s Developer Nation surveys, the number of developers has nearly doubled in four years:

- Q3 2021: 28.8 Million

- Q3 2023: 38.9 Million

- Q3 2025: 48.4 Million

The image below shows the progression:

Takeaway: If AI reduces the “cost per unit of software,” the most historically consistent outcome is more software, not less (the Jevons Paradox). More importantly, that very software still needs to be designed, operated, secured, audited, and maintained—i.e., the parts of the job that aren’t “just code.”

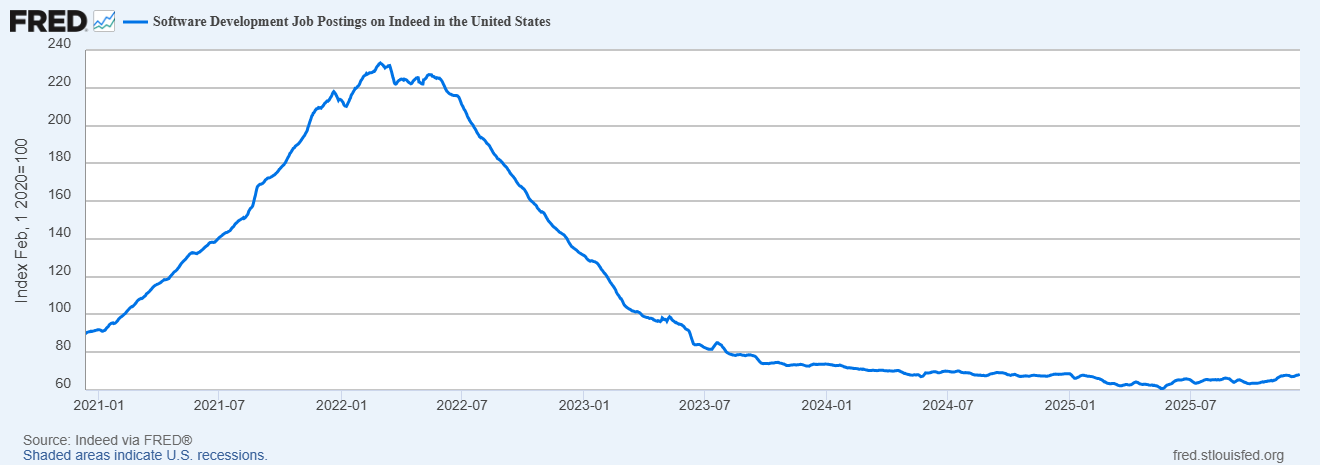

2) The labor-market chart needs context: the COVID spike distorts the story

The FRED/Indeed chart below is often used to prove the “collapse” of the industry. But it requires context.

What the curve actually says:

- There was a major run-up during the COVID-era boom (the peak visually dominates the chart).

- Then a sharp decline as interest rates rose and the “growth at all costs” era ended.

- After 2024, the series looks closer to stabilization, and by late 2025 it shows slight upward drift (e.g., 68.30 on 2025-12-12).

If you anchor on the COVID spike, you’ll read everything after as “collapse.” If you treat that spike as an outlier boom, the post-2024 pattern reads more like a market finding a new baseline.

However, this stabilization hides a qualitative shift. We are witnessing the decoupling of “coding” from “employment.” While the demand for full-time, US-based W-2 engineers has contracted, the population of people building software has exploded.

3) The Rise of “Vibe Coding” and Theory Loss

If the quantitative shift is about numbers, the qualitative shift is about method. We have entered the era of “Vibe Coding.”

Popularized by Andrej Karpathy, Vibe Coding describes a workflow where the human acts as a director rather than a mason. You don’t write loops; you “vibe” with the LLM. You paste a screenshot and say, “Make it look like this but pop more.” You describe intent, and the machine generates syntax.

This was made possible by the rapid commoditization of AI models. Using Claude Opus 4.5 today, for instance, is something impossible to think of (or explain) 10 years ago. It is important to stress that this way of working is in the hands of those who can affort tokens. Also they are gatekept by the FANGS of the world.

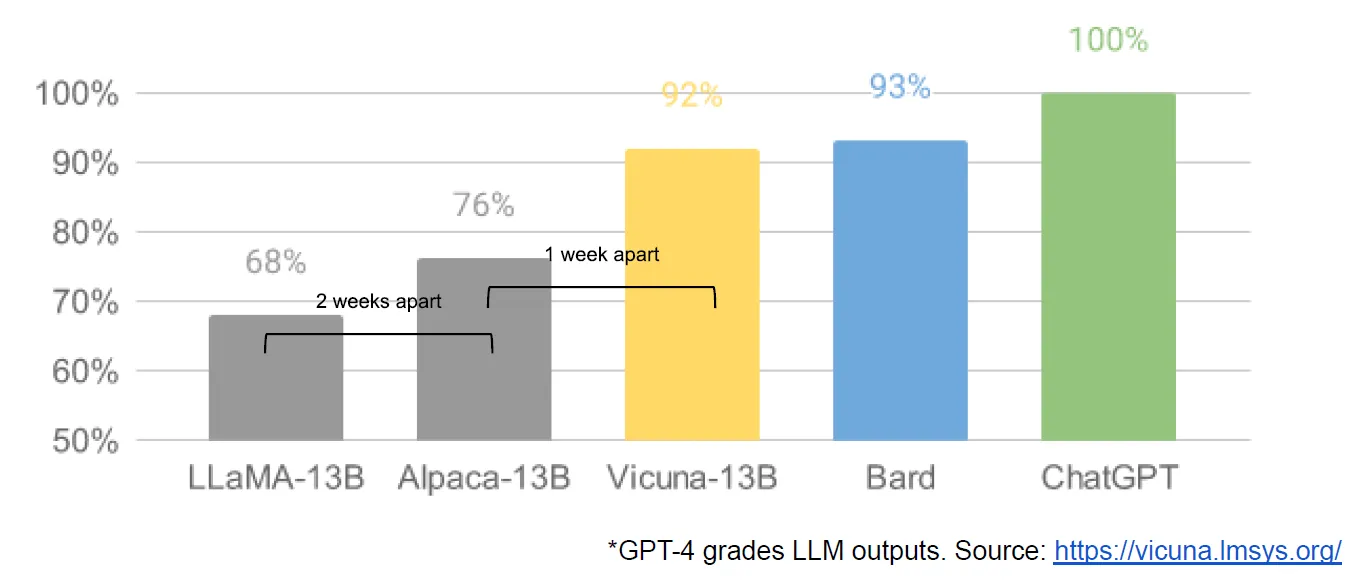

Open-source models, however, are improving at neck-breaking speed. As shown below, models like Vicuna-13B quickly reached 92% of ChatGPT’s quality, collapsing the moat between proprietary and open tools.

If we bring the chinese massive progress regarding AI, specially in the open-source scene, things become even more interesting. As DeepSeek-V3 states in its README:

DeepSeek-V3 stands as the best-performing open-source model, and also exhibits competitive performance against frontier closed-source models.

The power of open-source is already stablished in software development. It is paving the same way regarding AI. The famous Google’s Leaked “No Moat” Memo warned the company about that. The memo noted that open-source models were achieving results comparable to Google’s with significantly less time and capital investment. “Open-source models are faster, more customizable, more private, and pound-for-pound more capable”.

Regardless of the model, be it a paid or an open-source one, its usage has very low friction now. It clearly helps the development and production of software, so it becomes an inflection point. It is simply too slow to create something without AI from now on.

The Danger: Theory Loss

But this ease of generation brings a hidden risk: Theory Loss.

Peter Naur’s classic 1985 essay “Programming as Theory Building” argues that a program is not its source code. A program is a shared mental construct (a theory) that lives in the minds of the people who work on it.

- Old World: You built the theory by struggling with the syntax.

- New World (Vibe Coding): The AI generates the code. If you merely “approve” it without struggle, the mental model is never formed in your mind.

The software becomes a “zombie”: it works, but no one knows why or how to change it safely. This leads us to the central economic friction of the AI era.

4) The “new axis”: 95% of GenAI pilots fail — and verification cost is why

In a recent Forbes piece covering MIT research, the framing is blunt: 95% of custom GenAI tools fail to cross the pilot-to-production cliff.

Why? Because of the Verification Tax.

Generative AI is confidently wrong. If a model is 95% accurate, you still have to check 100% of its work to find the 5% of errors. The economic formula for AI adoption isn’t just about speed.

When systems are confidently wrong, people accumulate “Trust Debt.” They spend more time forensic-checking the AI’s output than they would have spent writing it themselves.

The Technological Response: Why TypeScript Won

This explains a startling statistic from GitHub’s Octoverse 2025: In August 2025, TypeScript overtook Python to become the #1 language on GitHub.

Why? Because Types are the automated payment of the Verification Tax. In a world where AI generates millions of lines of code, humans can no longer verify it all by reading. We need automated guardrails. TypeScript’s static type system rejects invalid code before it ever runs, preventing the AI from “hallucinating” artifacts that don’t exist. It turns the “Vibe” into a contract.

Additionally, types and interfaces are ground theory for any system. A seasoned software engineer can plan and architect using type-defined contracts that the AI will follow. This was good practice before AI-driven development, now it is a requirement.

5) Humans + AI beats either alone (and this is where “ROI” actually comes from)

So, how do we fix the failure rate? The answer lies in pairing.

OpenAI’s recent white paper on productivity impacts (GDPval) should be treated as part of the “human+agent pairing” evidence base. The research highlights that big gains appear when AI and experts work together, not when you try to replace humans outright.

On the Stack Overflow podcast, Pete Johnson (Field CTO, AI at MongoDB) reinforced this, noting that the “job killer” framing is flawed. He argues:

“You still own it… You’re still responsible for it running in production.”

Synthesis: The best ROI story is not “replace people,” it’s:

- Reduce cycle time on well-defined tasks (drafting).

- Keep experts responsible for correctness and system-level coherence (verification).

- Reinvest the productivity gains into more software and better operations (Jevons Paradox).

Every serious, corporate-grade line of code needs caring beyond text. For instance, systems still need customer feedback loops, support, investiment, decisions. It’s naive to belive that when you replace all developers with AI equivalents, you can just say:

“Oh, that’s wrong because of my AI. I am sorry, it will fix it”

You can’t say that specially when your software causes financial (or human) losses. Someone still has to “sign” and respond for it. Are C-class executives ready to fire all developers then take the fall for absolutely everything? I doubt it.

6) The JetBrains lens: some categories shrink, others expand

JetBrains’ Developer Ecosystem data reframes the workforce as a portfolio of activities, not just “dev count.” With ~20.8M professional developers in 2025, the work is redistributing.

My read of the likely shift:

- Fewer people needed in “first-draft” tasks (boilerplate, rote CRUD scaffolding, basic docs).

- More people needed in tasks that scale with output volume and risk:

- Evaluation & Testing: Building the “Accuracy Flywheels” that catch AI errors.

- Platform Engineering: Managing the infrastructure for 10x more services.

- Security & Compliance: Auditing the black box.

- Domain-Heavy Product Engineering: The “Theory Building” that AI cannot simulate.

This is the same “abstraction expands the surface area” dynamic—except now the abstraction is probabilistic and requires verification.

7) Final claim: If software eats the world, AI makes it hungrier

Software development is coordination across stakeholders (execs, product, support, legal, ops). If AI starts to mediate all of those interfaces—writing specs, drafting contracts, generating runbooks, then society doesn’t become less dependent on engineers.

It becomes more dependent on the people who can design, integrate, and operate AI-enabled systems end-to-end, with accountability.

The engineers of the future will not be those who can prompt the fastest, but those who can verify and plan the deepest.

What leaders should do

Finally some not-requested ideas for the future.

- Treat GenAI as a system, not a feature. Budget for evaluation, monitoring, and workflow redesign.

- Engineer for the verification tax. Make uncertainty explicit; build feedback loops (“accuracy flywheel”).

- Adopt “Safety-First” languages and tooling. The rise of TypeScript is a signal: use tools that automate verification.

- Pair AI with accountable experts. The “human + AI” combination is where gains compound.

- Measure transformation, not logins. Pilot success is redesign + adoption in real workflows, not just chat usage.

Additional Resources

- GitHub, The State of the Octoverse 2022: Global Tech Talent

- MIT Media Lab (Project NANDA), The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025

- HackerRank Blog, The Productivity Paradox of AI, 2025

- Microsoft Research, The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity, 2024

Note

This text has been edited by me and mostly written by AI models. I provided the ideas, my notes, the links to fetch information (which I have consumed myself previously) and the narravite I wanted. I iterated on the final text for quite some time. I also wrote parts of the text myself.